The Cromwellian Conquest

Oliver Cromwell, circa 1649 © National Portrait Gallery, London

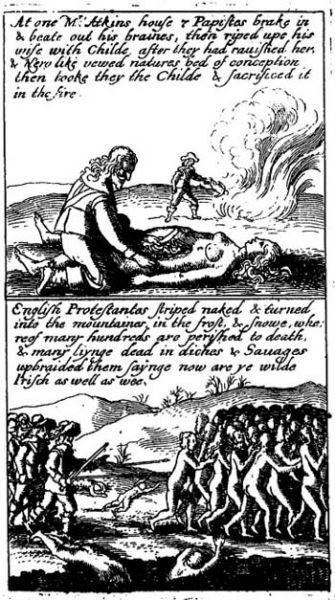

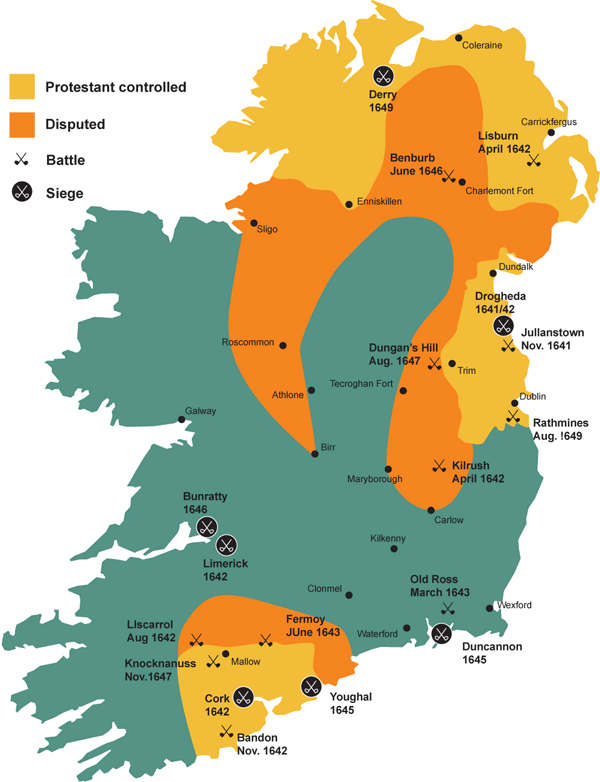

In October 1641, the native Irish in Ulster rose in rebellion in response to decades of widespread dispossession and dislocation, as well as systematic religious discrimination. Within months, the rising had spread throughout the kingdom, leading to the deaths of thousands of Protestant settlers, both English and Scottish, as well as similar numbers of Irish Catholics, killed in retaliatory actions by the colonial regime. The violence continued unabated for almost a year until the establishment of the Catholic confederate association in the late summer of 1642 helped restore order in large swathes of the country. The outbreak of civil war in England between king and parliament also prevented English military resources from reaching Ireland, forcing the colonial government to adopt a largely defensive strategy. For the next seven years, Ireland experienced a complex conflict involving confederate, royalist, parliamentary and Scottish forces. No one side could win an absolute victory but the execution of King Charles in January 1649 enabled the English parliament to focus exclusively on Ireland for the first time since 1642.

In March 1649, Westminster appointed Oliver Cromwell to lead an invasion of Ireland in order to crush all resistance to the new English Commonwealth and to avenge the alleged massacres of Protestant settlers in 1641-2. Irish land was also a valuable commodity, almost 70% of which was still held by Catholic landowners. Cromwell arrived in August, with 12,000 troops and a formidable train of siege artillery. Over the next four years his army defeated all military opposition in a series of bloody sieges and battles, which included the notorious massacres at Drogheda and Wexford in late 1649. Catholic Irish resistance proved very stubborn and the English army resorted to scorched earth tactics to deny the enemy any sustenance or shelter. Between 1650 and 1652 Ireland suffered a demographic disaster with up to 25% of the population dying as a result of deliberately induced famine, which also encouraged the spread of diseases such as dysentery and the plague.

By 1653, when the last formal surrenders of the war took place, the country had been devastated, the population decimated, the economic infrastructure destroyed. The English had effectively created a blank slate in Ireland onto which they now sought to project a new plantation society.

The Cromwellian Settlement

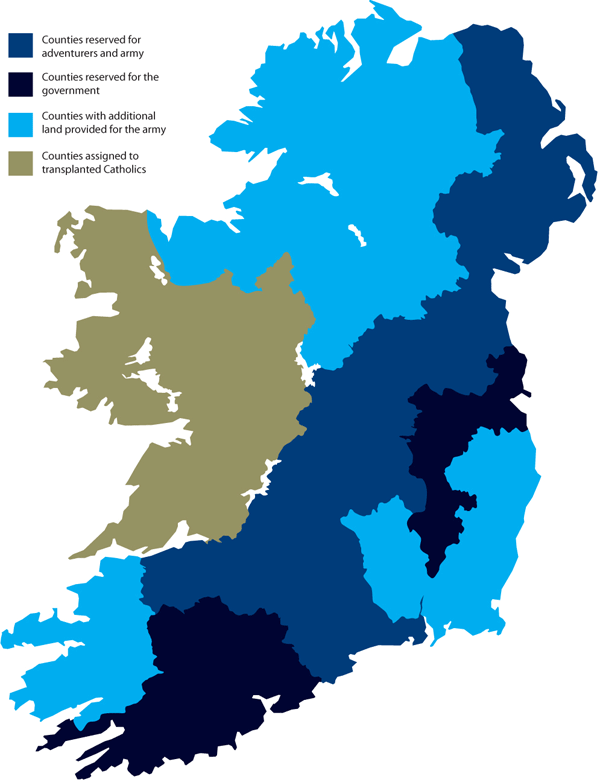

In March 1642, the Westminster parliament passed the Adventurers Act, which sought to raise money for the re-conquest of Ireland, using as security for the loans lands to be forfeited by the defeated Catholic rebels. The act was predicated on the unconditional surrender of the rebels and to ensure this, parliament alone could declare the war in Ireland to be at an end. The colonial government in Dublin received minimal assistance in 1642 as Parliament redirected the money to finance its war against King Charles in England. Nonetheless, the conquest of Ireland remained a necessity, particularly as in addition to the ‘adventurers’ parliament also promised during the course of the 1640s and early 1650s to pay English army arrears with Irish land.

As the war drew to a close in 1652, the English parliament passed the Act of Settlement, which specified who exactly would forfeit land in Ireland. The list included those who had taken part in or supported the initial rebellion in 1641-2, as well as anybody guilty of murdering civilians during the entire course of the conflict. The act also targeted prominent Catholic and royalist leaders, alongside Catholic clergy accused of inciting the rebels. Technically, almost the entire male Catholic population could have been encompassed within these terms but it soon became clear that the English parliament was more interested in dispossessing Catholic landowners than targeting those guilty of alleged crimes during the war.

In July 1653, the Commonwealth regime issued an order for the transplantation the following year of Catholic landowners across the Shannon to Connacht, the most isolated and poorest of the four Irish provinces. This order targeted thousands of landowners and their dependants but even the most recent research on the topic has failed to produce accurate figures for the numbers who actually moved into Connacht. Catholics, however, no longer retained any land east of the Shannon. In September 1653, two months after the transplantation order, the English parliament passed the Act of Satisfaction, which began the process of distributing forfeited lands among the adventurers and disbanded soldiers. In the first instance, the land would have to be accurately surveyed.

Civil Survey

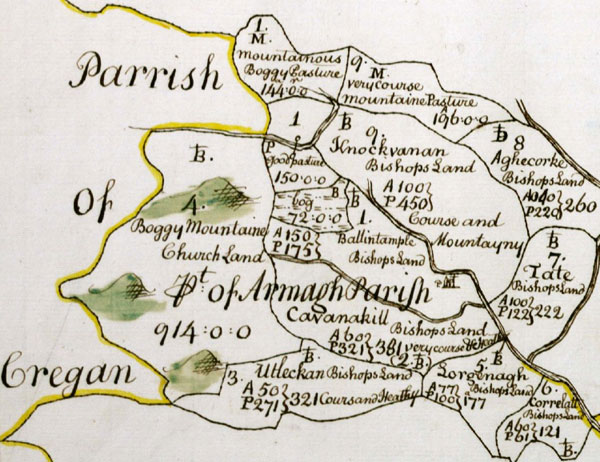

The Civil Survey, so called because it was ordered by the Civil Authority, was taken from 1654-6 in order to value the lands in Leinster, Munster, Ulster and Connaught assigned to satisfy the claims of soldiers for their arrears of pay during the Civil War, and of those Adventurers who made cash available in the 1640’s to pay for the war and were promised land in Ireland in return. Leitrim was the only county in Connaught surveyed as an earlier survey from the 1630s, the Strafford Survey, was available for most of the province.

The Civil Survey is a collation of landowner records, standardized to townland level. The value of each townland was determined as at 23 October 1641, the outbreak of the Rebellion. The valuations, collated and assembled in Dublin, were based on rents and improvements; buildings, mills and market days. The Civil Survey did not involve the making of maps, but a detailed boundary description was made for each barony and parish.

The Civil Survey, based as it was on the records of the original owners and not the result of an official or government survey, was considered by many of the new owners to be inaccurate and the Down Survey, so called because a chain was laid down and a scale made, was taken from 1656-8 under the direction of William Petty.

Down Survey

The Down Survey is a mapped survey. Using the Civil Survey as a guide, teams of surveyors, mainly former soldiers, were sent out under Petty’s direction to measure every townland to be forfeited to soldiers and adventurers. The resulting maps, made at a scale of 40 perches to one inch (the modern equivalent of 1:50,000), were the first systematic mapping of a large area on such a scale attempted anywhere. The primary purpose of these maps was to record the boundaries of each townland and to calculate their areas with great precision. The maps are also rich in other detail showing churches, roads, rivers, castles, houses and fortifications. Most towns are represented pictorially and the cartouches, the decorative titles, of each map in many cases reflect a specific characteristic of each barony.

Restoration Ireland

King Charles II, circa 1660-1665

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658 resulted in the collapse of the English experiment in republican government shortly afterwards. The restoration of Charles II in 1660 raised Catholic Irish expectations of recovering their lost lands but in November of that year the king published ‘a Gracious Declaration’ outlining his plans for Ireland. Charles acknowledged the ‘many difficulties, in providing for, and complying with the several interests and pretences there’, but highlighted the debt he owed to Protestant leaders in Ireland for facilitating the restoration of the monarchy. The declaration effectively established the year 1659 rather than 1641 as the benchmark for all future land claims, consolidating the Cromwellian land settlement in the process and dashing the hopes of Irish Catholics. Charles did make a number of individual provisions for close friends, particularly those who had shared the hardships of exile on the continent and in 1662 the Irish parliament, now an almost exclusively Protestant body, passed the Act of Settlement enabling dispossessed landowners to plead their case in a Court of Claims. Years of litigation followed as whenever the court ruled in favour of a Catholic the Cromwellian proprietors often refused to relinquish their holdings. Thousands of families never recovered their estates and a Catholic landowning elite only survived west of the Shannon in the province of Connacht, although this gradually disappeared over the following decades. By the middle of the eighteenth century the amount of land in Catholic ownership had declined to as little as 3% of the total. The land settlement of the 1650s, therefore, effectively established the Protestant Ascendancy class, which dominated social, economic and political life in Ireland for over 200 years until the great land reforms of the second half of the nineteenth century.